Strategic dependencies demand a new, strategic approach towards the photovoltaic industry in Europe.

The disruption of global value chains by the pandemic, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, has dramatically exposed the risks of globalization: shortages of essential goods, production chains undermined by the lack of critical raw materials (CRM) and components, ‘weaponized interdependence’, and technology wars.

These are key features of the new global economy, increasingly divided between two competing blocs, the United States and China, with the European Union still struggling to define its role. In this context, decarbonization and the transition to renewable energies become even more pressing. Especially for the EU, the urgency of achieving ambitious climate targets is compounded by the need to reduce dependence on economies that control fossil fuels, to minimise the rents accrued and related geopolitical leverage.

Yet the transition to renewables is constrained by the asymmetric distribution of raw materials, manufacturing capacities, and technological capabilities. China has experienced an astonishing technological catch-up, gaining dominant shares in strategic markets such as photovoltaic panels and lithium batteries. Now the US and the EU are realizing that strategic dependencies on a few suppliers of essential CRMs and intermediate goods can undermine growth prospects and push away their energy-transition targets.

After three decades of eschewing trade regulation to govern the global division of labor and associated productive and technological specialization, forgotten concepts—‘absolute advantage’, idiosyncratic capabilities, selective industrial policy, ‘strategic autonomy’, and ‘technological sovereignty’—are once more to the fore, even in Brussels. A theoretical rationale and empirical evidence are needed to support industrial policies to strengthen economies in strategic domains, including those related to the green transition. For the EU, these policies are essential to avoid switching from one dependency—on fossil fuels and their suppliers—to another: on CRM and the components required by green technologies.

Become part of our Community of Thought Leaders

Get fresh perspectives delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for our newsletter to receive thought-provoking opinion articles and expert analysis on the most pressing political, economic, and social issues of our time. Join our community of engaged readers and be a part of the conversation.

Photovoltaic supply chain

The photovoltaic supply chain (PVSC) is crucial to achieving climate goals. This is due to the increasing performance of PV panels, their ductility (the manipulability that makes them suitable for myriad civil and industrial settings), and the efficiency of their manufacture (which allows the associated emissions to be netted off relatively quickly in use).

Global installed solar PV capacity is expected nearly to triple by 2027, to a cumulative 1,500 gigawatts, surpassing natural gas as well as coal. According to the EU Green Deal’s climate targets, the PV industry is expected to provide a massive contribution, with a new capacity of 325-75 GWDC by 2030. This would require a three- to five-fold growth of the European market compared with 2019.

With the war-induced energy crisis, EU plans became even more ambitious. The Solar Energy Strategy published in May last year set out new targets: additional capacity of 400 GWDC by 2025 and nearly 750 GWDC by 2030. This means more than doubling EU capacity by 2025, from 170GWDC in 2020, as well as meeting the Green Deal’s already challenging targets. The EU’s ability to strengthen its production and technological capacities along the PVSA will determine whether it can reach these targets—or end up facing new and stronger strategic dependencies.

During the last decade and a half, the PVSC has seen growing market concentration, reshuffling productive and technological hierarchies. Western dependencies have grown with the rise of China and the relative retreat of the US and the EU as global players. In 2021 China’s share of critical production elements reached 75 percent in modules, 79 percent in polysilicon, 97 percent in wafers (the substrates for microelectronic devices), and 81 percent in solar cells.

This explains the proliferation of industrial-policy initiatives, such as with the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Solar Energy Strategy, aiming to increase manufacturing capacity, consolidate technological capabilities, and reduce dependence on China. Being key players in competition, though, their strategies on industry and trade can complicate the picture.

Strategic dependencies

A systematic and detailed understanding of the PVSC is essential to support the design and implementation of supportive industrial policies. In a recent work, we assess the long-term evolution of trade and technological hierarchies, highlighting polarisation and strategic dependencies. This allows us to zoom in on critical products and related technologies.

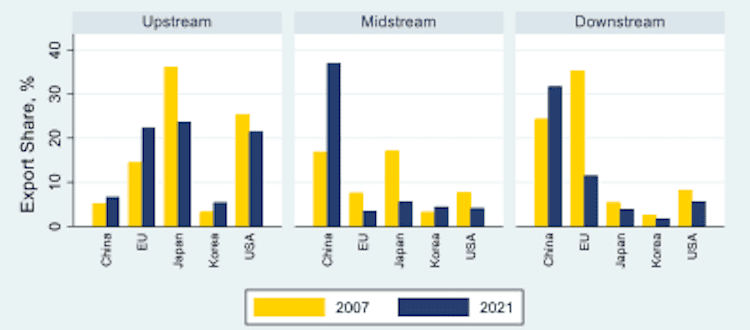

Figure 1 shows how the PVSC has evolved over 2007-21, focusing on down–, mid-, and upstream segments. The rise of China as a leading player emerges everywhere except upstream, where the EU, Japan, and, to a lesser extent, the US have managed to maintain competitive positions.

Focusing on bilateral relationships, the EU and the US display a growing dependency on China, particularly in the mid and downstream segments. While the Chinese import share keeps increasing for the EU, ‘decoupling’ seems however to be emerging with respect to the US. In about a decade (2011-21), the Chinese share in US imports fell from 35 percent to 8 percent in the midstream and from 40 percent to 25 percent in the downstream—still the most exposed segment as far as the US is concerned. This may be related to the anti-dumping policies introduced by the US International Trade Commission in 2012.

Support Progressive Ideas: Become a Social Europe Member!

Support independent publishing and progressive ideas by becoming a Social Europe member for less than 5 Euros per month. You can help us create more high-quality articles, podcasts, and videos that challenge conventional thinking and foster a more informed and democratic society. Join us in our mission – your support makes all the difference!

In the midstream, the EU trade deficit reached a peak of €30 billion per year in 2021—Chinese supplies have come to exceed 60 percent of total EU imports and are projected towards 80 percent (in the downstream, the China share of EU imports comes close to 60 percent). While China shows a growing deficit in the upstream (in machinery, for instance), its three main suppliers—the EU, Japan, and the US—hold fairly similar shares, reducing dependence on anyone.

On the technological side, China is still closing the gap but is quickly scaling up in technologies linked to upstream goods. This casts doubts on the ability of its competitors, particularly the EU—previously one of the technological leaders—to maintain their positions in that segment. The Revealed Technological Advantage indicator (above 1 when the country displays relative specialization in a specific domain) shows China’s catching up (Figure 2), while Japan and Korea seem to maintain relatively strong positions, unlike the US and EU.

Figure 2: Revealed Technology Advantage index by country, 2007-19

Combining trade and technology data to provide evidence on specific products and technologies highlights the pinch points on import dependence and technological vulnerability. For the EU, three fundamental components are highly critical: cells and modules, solar glass, and inverters (from the direct current generated to the alternating current consumed). It is similar for the US, albeit better-concerning cells and worse for wafers and related machinery. It is here selective industrial and innovation policies seem most urgent. In the safe area of low import dependence and strong technological capabilities fall only polysilicon and DC generators for the EU and silver paste (for conductivity) and polysilicon for the US.

Policy implications

Our results have implications for policy and practice. Strategic dependencies and technological sovereignty should be addressed in the design and implementation of objectives and instruments—particularly now that once-neglected concepts, such as mission-oriented and transformative approaches, mean strategic, selective industrial policies are back in vogue. Paradigmatic examples include the Solar Energy Strategy and the Green Deal Industrial Plan, which aim to strengthen the EU’s productive and technological capabilities in key sectors.

EU dependencies in solar are the result of radically different industrial policies put in place by major international players. Theoretically, the union could seek to achieve its environmental targets by adopting a ‘buy from abroad’ strategy towards environmental technologies and green goods and services. But this would only enhance these strategic dependencies.

The EU’s climate strategy should instead fully integrate the goal of fostering the European technological and production capabilities needed for the decarbonization of the economy. This requires adapting the framework of industrial and innovation policies accordingly, while also pursuing greater co-ordination with trade and foreign policies. The PV industry will be one of the most relevant candidates to apply and test the effectiveness of this approach—where climate objectives, technological sovereignty, and strategic autonomy go hand in hand to maximize sustainability, security, and the growth opportunities of green transformation.